Policing works best when the public grants trust to the police. That trust is inherently fragile … If law enforcement executives erect too many barriers to transparency, we may find our political masters pulling them down.

— Mike Wallentine, West Jordan police chief

OPINION — In 2018, a Utah teenager named Zane James was run over and then shot and killed by a police officer. Utah’s attorney general later ruled the shooting was justified.

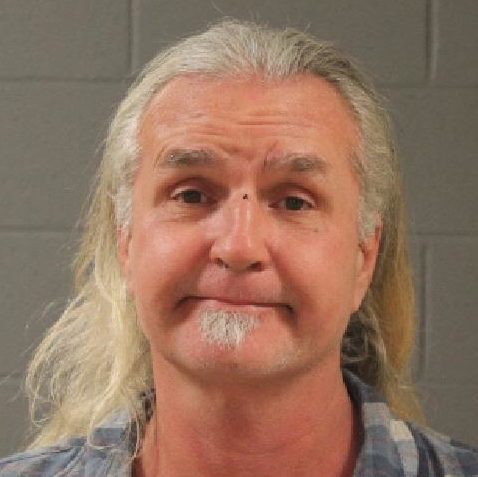

The Salt Lake Tribune requested the Garrity statement, or internal interview, that Cottonwood Heights Police Officer Casey Davies provided after he killed James. Cottonwood Heights declined The Tribune’s request, but the James family received the report.

The public later learned the Garrity report contradicts the story police told after the shooting happened in 2018, thanks to the James family’s disclosure. Police failed to tell the public that Davies ran James over before killing him.

The Davies interview is just one of dozens of Garrity statements The Salt Lake Tribune requested over the course of the last year. Many municipalities, including several in Southern Utah, have provided requested materials.

However, Washington County Sheriff’s Office did not. The state records committee reviewed the denial and ordered the agency to turn over the requested materials.

Instead, the county took The Tribune to court to prevent their release. At a cost that will exceed six figures, the newspaper is fighting three municipalities to preserve public records that should have been released because they belong to the public.

Since 2004, there have been 350 police shootings in Utah. Prosecutors have so far found the shooting to be unjustified in 18 of those cases, or 5%, though several cases are still under review. In just seven of those 18 cases criminal charges were filed, and only one of those charges resulted in any form of conviction — a guilty plea to a charge of official misconduct.

Utah’s criminal laws are “more generous to law enforcement officers than to other members of our community,” Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said in 2021.

If the vast majority of shootings in Utah proceed in accordance with department policy, if internal investigations are thorough, and if department policies adhere to best practices, then departments and involved officers should want those exonerating records released.

If records reveal internal investigations or department policies are lacking, that is well within the public’s right to know.

As taxpayers, we are employers of the police department. And a secret review process of a state actor’s use of deadly force is bad public policy. The residents of Utah deserve to know the investigative steps that were taken, how the relevant policies were applied, and what the conclusion was.

And yet, Utah lawmakers plan to introduce legislation during the upcoming session that will make Garrity statements private.

Proponents of this legislation say releasing records to the public significantly compromises policing. But the dozens of agencies that shared Garrity reports with The Tribune have continued to function following their release of records. More broadly, hundreds (if not thousands) of other departments regularly provide these records in states where disclosure is the established norm.

You may be wondering why we are so interested in these records.

Well, journalists in Utah have maintained a police shootings database for 17 years. This year, Tribune reporters sought to expand it to look at how, when, why, where, and against whom the police use deadly force, necessitating the Garrity requests.

No other organization in the state — governmental or otherwise — is meaningfully engaged in this work. The Utah Attorney General’s office has represented that it is working to review police shootings and collecting documents from agencies around the state. This is the second time they’ve made this promise in three years.

While the public waits, journalists are doing the urgent, necessary work of documenting, analyzing and reporting on these cases.

There is no act that potentially violates public trust more than a police shooting.

We’ll let you know when the hearing is for this legislation, so you may join us, the James family and others in supporting transparent and open government in Utah.

The following Southern Utah-based governmental entities released related records in 2021:

- Hurricane Police Department

- Parowan Police Department

- Santa Clara/Ivins Police Department

- Washington City Police Department

Well over half of the country’s 50 states have determined Garrity reports are public, awarding them to requestors, including conservative-leaning states like Florida, Arizona and Texas.

What is a Garrity statement?

Garrity v. New Jersey (1967) is a Supreme Court decision that gives law enforcement officers under criminal investigation the same protections under the 5th and 14th Amendments as all Americans. It also provides their police departments with the ability to legally compel them to make a statement and otherwise cooperate with an internal investigation. Garrity statements cannot be used in a criminal proceeding.

The Garrity interview sets aside the question of whether an officer committed a crime and looks at whether the officer acted within the use-of-force policies of the department. Policies can require officers deescalate situations before engaging in deadly force or that officers intercede if they believe another officer’s force is excessive. They can also ban certain uses of force, such as firing at or from a moving vehicle.

Submitted by THE SALT LAKE TRIBUNE EDITORIAL BOARD.

Letters to the Editor are not the product of St. George News, its editors, staff or news contributors. The matters stated and opinions given are the responsibility of the person submitting them. They do not reflect the product or opinion of St. George News and are given only light edit for technical style and formatting.