FEATURE – Where Sun River is today once stood a “one-family village.”

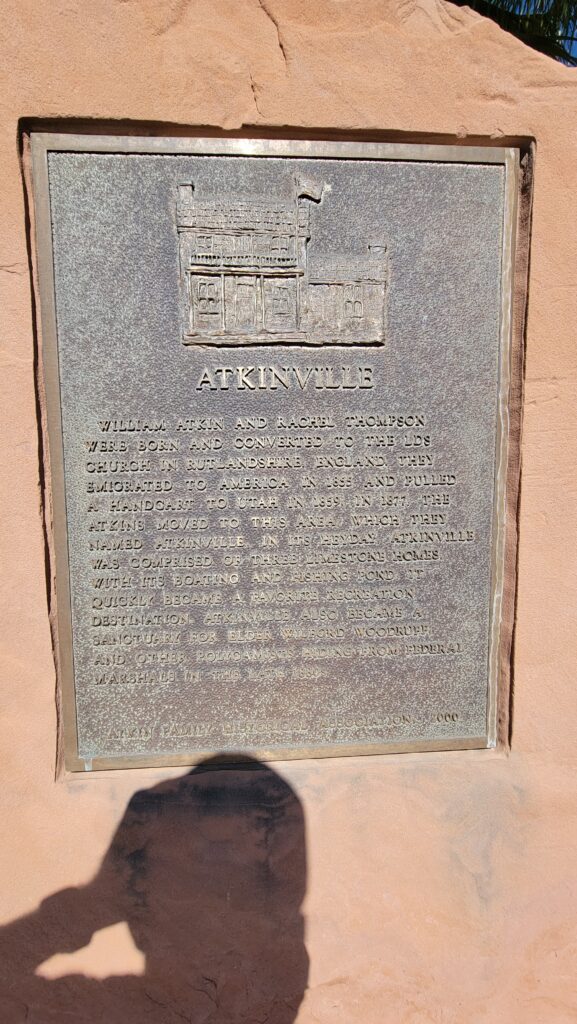

Unfortunately, there are practically no traces left of the little village on the landscape. The only reminders for today’s visitors are a monument erected by descendants of the family who established the town next to the Sun River clubhouse and the name of a park where another plaque dedicated to the memory of these hardy, early Dixie pioneers will soon stand.

The Atkin’s early life

Both William and Rachel Thompson Atkin were born in Rutlandshire, England, he in Empingham and she in Barrowden. They joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints independently of one another. Rachel was baptized in 1849 and William in 1852. They met at church functions and were married on December 18, 1854. They sailed to the United States on the ship Siddons in 1855, landing in Philadelphia, where they remained for four years to earn enough money for their overland journey. They then came west with a handcart company, arriving in Salt Lake City in November 1859.

In Salt Lake City, William served first as a laborer, earning enough money to buy a lot and subdivide it to build a house for he and his family and rented out the other homes as a source of income. He eventually opened a butcher shop near his home and served as a bodyguard to Brigham Young for a period. While in Salt Lake City, he also learned the stonemason trade and spent his final year there as a road supervisor.

The call to Dixie

In 1868, William and Rachel Atkin received the call to help settle Utah’s Dixie. When they first arrived, they lived in St. George. Reid L. Neilson wrote in his book “From the Green Hills of England to the Red Hills of Dixie: The Story of William and Rachel Thompson Atkin.” that they bought lots and built a home by stacking rectangular grass sods in brick-like fashion, which was sufficient for their first year,

William helped farm sugar cane for Molasses in Cooper Bottom southwest of St. George. He also served as a stone mason on the St. George Tabernacle, cutting and shaping the natural red sandstone. It was this skill that presumably led to his call south. Once the Tabernacle was finished, he also served as a stone mason in the construction of the St. George Temple.

The Atkins farmed in Heberville (today’s Bloomington) in a cooperative with other families. Eventually, because his work on the temple often took him away from farming, he sold his interests in that operation for some land in Santa Clara, Neilson noted.

In 1875, the family became part of the United Order of Heberville, which Brigham Young renamed Price City. The Atkins already owned land there and helped the United Order build sheds, corrals and a communal dining halls. They also assisted in planting 500 apple trees, 200 peach trees and fields of alfalfa, Neilson wrote. Members of the United Order were rebaptized as a signal of their commitment. William was rebaptized, but Rachel was not. Despite its best intentions, the United Order disbanded in March 1877. Human nature was the underlying cause of its failure with inevitable jealousies and suspicions as well as some members joining mainly because of social pressure and no real conversion to the idea, Neilson explained.

The move to Atkinville

After fulfilling their mission to work on the tabernacle and temple, the Atkins moved to Atkinville in 1877. It was an uninhabited stretch of arable land on the east bank of the Virgin River eight miles south of St. George.

“The place where we live is called by our name, Atkinville, because we were the first that took it up when it had never been used by man that anyone knows and we have made it a beautiful place and me and the boys own it all, about 160 acres,” William wrote in a letter to his sister-in-law still living in England.

The Atkins built a large limestone home for their growing family and cultivated the surrounding soil. Soon William’s brother and sister-in-law, Henry and Selena Atkin, and his sister and brother-in-law, William and Adelaide Laxton, joined them in Atkinville, thereby creating a “one-family village,” Neilson wrote.

The family dug a 1.5-mile ditch from the river after constructing a diversion dam. There was also a spring on the north portion of the property. Eventually, the spring and ditch accumulated and created a shallow pond, Neilson wrote.

Atkinville consisted of three limestone homes for the three families as well as cellars, livestock corrals, hay and grain stack yards, a granary and several pigpens and chicken coops. William and Rachel’s home featured a large porch, a balcony deck, a flower garden, a bowery shed and a parlor with an organ.

The family grew wheat, barley and alfalfa. For a period of their stay, William would travel to St. George to work as a stone mason while his sons, William III, Joseph, Henry and John, would tend to the farm. Rachel raised chickens, made butter and was in charge of all domestic duties. In the winter, the boys would haul wood and sell it, usually not for cash but for some sort of scrip at St. George businesses, Neilson explained. They also cut ice from their pond and stored it wrapped in straw in small caves on their property.

The pond became an unofficial resort that attracted residents from all over Utah’s Dixie, soon becoming a popular picnic, recreation and fishing destination.

“Not only did it provide the fish for us, but we were able to catch some for market,” the Atkins’ son Joseph wrote about the pond. “I have often caught enough in the evening to sell for $2.50. It finally got so father could stay at home and make a trip each week to St. George with produce and get a neat amount of cash.”

The isolation came with advantages. William and his sons grazed cattle on the nearby hills, uninhibited by city restrictions and property lines. They built up a significant cattle operation with a summer range in the Bull Valley mountains then later Cedar Mountain.

Later, adding to their herd of cattle came sheep. Helping a nomadic sheepherder drive his herd to the Colorado River led to the acquisition of a few sheep that eventually swelled to a herd of 1,700.

A Refuge for the Senior Apostle

One of Atkinville’s claims to fame is serving as a refuge for Wilford Woodruff from 1885-1887 At the time, Woodruff was the senior apostle of the Mormon church and the would-be successor to John Taylor, third president of the church. As a polygamist, Woodruff was a target of federal marshals and sought an isolated place to hide to avoid capture.

Though it is not known for sure, the Atkins probably met Woodruff when he served as the first president of the St. George Temple. Woodruff forged a very close relationship with the Atkins through the experience, becoming an honorary family member, whom the Atkin children called “Grandpa Woodruff.”

The apostle did not exclusively stay in Atkinville during this period but also spent some time in Bunkerville, Nevada, and in the homes of trusted friends in St. George. He did make a few trips north to Salt Lake City during this time, one in particular to attend to his first wife, Phoebe, on her deathbed. He didn’t even attend her funeral for fear of capture. His second wife, Emma, and youngest daughter, Mary Alice, spent three months in Atkinville with him starting in November 1886, but most of the time, he was without family there.

He enjoyed Atkinville for its outdoor recreation opportunities: fishing and hunting. According to Neilson, on one occasion he caught 60 chub in one day in the pond. He also enjoyed hunting doves, ducks, quail and jackrabbits.

As a settlement with one of the highest percentages of plural marriages, St. George experienced regular polygamist raids, but Atkinville provided a comfortable eight-mile buffer, Neilson wrote. The roads into Atkinville provided an easy chance to survey for approaching danger and the nearby Arizona strip was a good hiding place if marshals encroached.

In his book, Neilson related one close call Woodruff experienced while in Atkinville. When the Atkins youngest daughter, Nellie, spotted the buggy of federal marshals in the distance, they quickly gathered Woodruff’s bedroll, food, water, books and fishing tackle and sent him into the pond on a special boat, which they pushed into cattails and rushes that lined the pond’s perimeter.

When questioned about the ability of the federal marshals to spot him from a nearby bluff, Woodruff reportedly replied “that there were plenty of places to hide where neither the marshals from the hill, the devil from below nor the Lord from above could see his boat.” When the coast was clear, William reportedly signaled Woodruff back with a duck call.

While there, Woodruff was anything but idle. He attended to church business by writing a vast amount of official correspondence as well as many letters to friends, family and civic authorities. He also helped with farm chores and put food on the table through his hunting and fishing. He helped shear the Atkin sheep.

On July 12, 1887, he left Atkinville for the last time after hearing of the grave condition of John Taylor, who would die on July 25. As the senior apostle, Woodruff succeeded Taylor, officially being sustained as the fourth president of the church in April 1889. In 1890, Woodruff’s administration issued what became known as “The Manifesto,” which stated that the church would comply with the law of the land and no longer endorse or practice plural marriage.

Though they provided a refuge for many other polygamists, William and Rachel never entered into the practice themselves. From some reports, Rachel would have none of it when church elders asked William if he would take on another wife. She said that if it happened, she would return to England and never be heard from again and William knew she meant it, Neilson explained. The Atkins used their free agency by not practicing plural marriage and felt their contribution to the kingdom by harboring polygamists showed their devotion to the church and its leaders, Neilson noted.

In a letter to the Atkins on January 30, 1889, Woodruff wrote longingly of his time in Atkinville, joking: “I don’t think the ducks or fish in your pond are looking for any more trouble from me. Yet I would like to look at them some more.”

Woodruff died on September 2, 1898.

Return to St. George

In the fall of 1890, William and Rachel moved back to St. George, where they remained until their deaths. Two of their sons remained in Atkinville, but they, too, ended up in St. George soon after.

Neilson wrote that the Atkins enjoyed not being isolated any more.

William served as a St. George Temple worker the rest of his life. He also became a news writer for “The Union” newspaper, recounting sermons and writing editorials about the issues of the day.

William died on May 22, 1900 and Rachel followed three years later.

“William and Rachel were hardy individuals who endured good times and bad times,” Neilson wrote of the couple. “They put as much energy into their church callings as they did into their daily chores. Through their explicit teachings as well as their examples, their posterity learned, and continues to learn, many valuable lessons.”

Remembering Atkinville

A 1906 flood destroyed Atkinville’s buildings. Thankfully, its memory is preserved in a replica of the William and Rachel Atkin home constructed at This is the Place Heritage Park in Salt Lake City in 2001. Some of the original foundation stones were used in its construction.

There is no trace of the former home on the landscape in Sun River. Its former location is now a patch of gravel next to the Sun River Golf Course. The Atkins’ alfalfa fields are now fairways.

A group of descendants of William and Rachel, the Atkin Family Historical Association, erected a monument interpreting Atkinville next to the Sun River clubhouse in 2000. The Association published Neilson’s book the same year.

Members of the Daughters of Utah Pioneer Camp in Sun River insisted their name be the Atkinville Camp because they live where the village once stood. Since 2004, the Atkinville Camp has wanted to erect their own plaque in remembrance of Atkinville but did not know where they would put it. When St. George City proposed a park in the area, Camp members felt it was the perfect place, Camp Captain Lorraine Rice said.

The park’s original name was to be “Legacy” but because of the DUP Camp’s proposal it became the “Atkinville Wash Park.” The International DUP organization paid for the plaque and St. George City will pay for the mounting of the plaque, Rice said.

The ceremony dedicating the plaque will be held in November, which will also double as a celebration of the 1ooth anniversary of the Washington County DUP Company, which is home to seven camps.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

William and Rachel Atkin proved themselves as hardy Dixie pioneers, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

This historic photo shows a gathering at William and Rachel Atkins limestone home in Atkinville, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

This historic photo shows what the Atkinville pond looked like, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

This painting by Julia Nielson depicts what Atkinville looked like during its heyday | image courtesy of Julia Nielson, St. George News

Wilford Woodruff used Atkinville as a refuge from federal marshals seeking to capture him for practicing polygamy, date unspecified | Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Descendants of William and Rachel Atkin erected this monument next to the Sun River Clubhouse in 2000, Oct. 2, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Descendants of William and Rachel Atkin erected this monument next to the Sun River Clubhouse in 2000, Oct. 2, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This gravel patch next to the Sun River Golf Course is where William and Rachel Atkins home once stood, Oct. 2, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page, follow his Instagram account or subscribe to his YouTube channel.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2021, all rights reserved.