FEATURE — “It looks like the good Lord took everything left over from the creation, dumped it here, then set it on fire.”

That is thought to have been how local historian Juanita Brooks once described Snow Canyon.

Visitors today might disagree with her assessment, but on the other hand, it does have validity. Snow Canyon State Park is a prime example of Washington County’s stark landscape contrasts.

For instance, at the north end of the park, a volcanic ridge lines the east side of the road while the west side is a showcase of rolling red sandstone hills, some with a checkerboard pattern and others more smooth.

And smack dab in the middle of that striking sandstone sit large chunks of black volcanic rock, as if they somehow escaped their kin on the east side to bask in relative solitude.

Farther north those crimson petrified sand dunes give way to white sandstone knolls.

At the south end of the park lie actual sand dunes of the nonpetrified variety. The park also boasts lava tubes, slot canyons and an arch that rivals those found in Arches National Park.

In short, it is no surprise this geologic spectacle became one of Utah’s first state parks in 1957.

Geologic history

Snow Canyon is located at the meeting place of three geophysical areas, the Great Basin Desert, the Mojave Desert and the Colorado Plateau.

Approximately 183-173 million years ago, winds swept up massive dunes that eventually covered what is now Snow Canyon. These dunes, as much as 2,500 feet thick, gradually cemented into the Navajo Sandstone visitors see today. This stone layer is made up of grains of the same thing one sees in a modern dune or beach, light-colored quartz sand.

While this type of sandstone is the most commonly seen layer of rock in the park, its appearance is not uniform in both color and texture. The color of the sandstone correlates to the amount of iron oxide, or rust, in it. Time, erosion and other forces have weathered the sandstone in different ways, making their appearance anywhere from smooth and rounded to increasingly fractured with patterns that resemble alligator skin.

In geologic time, the sandstone would be a senior citizen but the volcanic rock is a geologic toddler.

Approximately 1.4 million years ago and as recently as 27,000 years ago, nearby cinder cones erupted and began spewing channels of hot, molten rock that found its way into the area’s lower places such as stream beds and valleys, covering everything in its path. Quickly hardening into basalt, these former lava rivers formed thick layers of rock that are more resistant to weathering that obstructed the paths of streams and rivers, which then started to take paths of least resistance to carve new routes through the softer Navajo Sandstone.

Over time, erosive forces formed steep canyons, making a spot once at a topographic low a topographic high, creating some inverted topography, according to geologists. In Snow Canyon, for instance, lava-capped ridges were once canyon bottoms.

Another phenomenon resulting from these geologic processes is sets of large basalt chunks sitting atop flowing Navajo Sandstone a significant distance away from the black ridges and outcroppings from where it originated.

Early native and pioneer history

Evidence of Native American use of Snow Canyon exists as far back as 500 B.C. in the form of arrowheads, pottery shards, grinding stones, fire pits and petroglyphs. There is no evidence the Anasazi or Ancestral Puebloan people, who were in the area from 100 A.D. to 1250 A.D., lived in the park permanently. Most likely, they just passed through the area and utilized it for some hunting and gathering, passing through between their summer and winter grounds.

Southern Paiutes used the canyon for hunting deer and rabbits as well as gathering seeds, roots, nuts and berries from 1200 A.D. into the mid-19th century.

The story goes that Snow Canyon was “discovered” by early settlers in the 1850s who were looking for lost cattle, a story duplicated for other areas of scenic merit within the state of Utah. Apparently, some pioneers grazed herds in what is now the park thereafter.

Anyone who knows any inkling of Southern Utah’s history knows that the early settlers did not have a “walk in the park” to tame the area’s harshness, including its extreme temperatures, flood potential, poor soils and relative isolation. Under those conditions, it’s no wonder that these Dixie pioneers would seek some type of recreation, and they found it in Snow Canyon’s Johnson Canyon, formerly known as “Volcanic Kanyon” through picnicking and rock scrambling near Johnson Arch, named for pioneer horticulturalist Joseph Ellis Johnson, which was a popular spot for such outings.

As a result of the canyon’s great acoustics, the story is told Maude Johnson, the very daughter of the canyon and arch’s namesake, climbed up under the arch to sing as a form of entertainment for picnickers in the early 1870s.

A bit later, some local pioneers made their own “petroglyphs” by writing their names in wagon axle grease. The names, easily readable on the sandstone, date back to 1881.

Visitors, however, cannot help but ask the question, “What were the settlers doing up there?”

Snow Canyon State Park naturalist Jenny Dawn Stucki said that the purpose for their visit is sheer speculation but that she believes they were there camping for recreation and decided “to ‘mark’ their moment and celebrate being together in such a beautiful area.”

The other possibility, she said, is they were attending to a cattle herd, possibly the town of Santa Clara’s town herd, as pioneer journals indicate there could have been.

“During early settlement here, many individual families had only one or two cows; many were unfenced for various reasons,” Stucki said. “So one solution for the cow conflict was for the town people to combine all the cows into one ‘town herd’ and take the cows out to areas where they could graze away from town.”

The town’s young men would take turns watching the herd graze during the day, and the location of where the names are written in sandstone “would have been a nice shady place to hang out,” Stucki remarked.

State park status

Most would probably consider Orval Hafen as one of the most significant people in Snow Canyon’s most recent history. A visionary, Hafen saw the St. George area as a tourist mecca before most figured out that the area’s mild winter climate and stunning surrounding scenery could be its two best commodities.

As a Utah State Senator, Hafen played an integral role in creating the state park system and adding Snow Canyon as one of its first inclusions. Washington County Commissioners Rudger Atkin and Jim Lundberg were two of Hafen’s best allies and encouraged Harold Fabian of the State Park Commission to visit the spectacle of sandstone and lava rock located only a short distance from downtown St. George. With the Commission convinced, negotiations began on private property necessary for the creation of the park.

Washington County donated nearly 300 acres towards the park and later the Bureau of Land Management transferred title of 3,854 acres to the state for the same purpose.

The park was originally called Dixie State Park, but that name gave way to one that honored pioneer leaders Lorenzo and Erastus Snow.

A highway through the park was graded and graveled in 1958, and 1974 brought the first phase of development on the park’s campground. The road was paved through the canyon in 1977, and by 1984 modern restrooms and showers were added to the campground.

Snow Canyon has served as the backdrop for several well-known western movies, including “A King and Four Queens,” starring Clark Gable, “The Conqueror” with John Wayne and Susan Hayward as well as several films starring Robert Redford, including “Jeremiah Johnson,” “The Electric Horseman,” with Jane Fonda and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” with Paul Newman.

Snow Canyon today

In 2012, there was a hullabaloo over park management — a local group wanted to take over administration of the park from the state, which was in concert with the push at the time for Utah to take over federal lands within its borders. Utah State Senator Don Ipson, of St. George, was even ready to draft legislation to transfer management of the park over to Washington County or a consortium that including the county and some of the neighboring municipalities, something that never came to fruition.

One of the sticking points of the locals was a reduction or elimination of fees for the local population, especially Washington County residents who simply wanted to drive through. It was heated for a while, but Stucki said all parties came to an agreement.

“A joint management committee was formed with one representative from Washington County, Ivins, St. George, Santa Clara and Snow Canyon State Park (Park Manager, Kristen Comella),” Stucki said. “These five members meet quarterly to discuss management issues. As part of this process, a nine-member ‘Citizen Advisory Team’ was created with representatives from the surrounding area and various user groups.”

Stucki said since these two bodies have formed, conflicts have been resolved and all is working well.

At about the time of the disagreement over park management, the organization Friends of Snow Canyon was formed to help support the park financially, help with park maintenance and sponsor educational programs for area schools.

Park visitation has increased steadily over the past six years by an average of 12 percent annually during that time period, Stucki noted.

As one of the few Utah state parks designated solely for its natural beauty, Snow Canyon is a little different than Zion, its national park neighbor. While Zion’s map is full of names for its striking stone monoliths such as The Great White Throne, The Watchman and the Three Patriarchs, Snow Canyon’s map is devoid of such names. Johnson Arch and Jenny’s Canyon are a few exceptions, but they are simply named after people.

“We don’t name park features,” Stucki said. “We let peoples’ imaginations be inspired with their own individual experiences with the formations and monoliths they discover here.”

So visitors can give park formations their own names, and the next group of visitors might name a formation something completely different. And that’s OK.

At least they’re giving the park’s memorable monuments a personality.

Visiting Snow Canyon

The 7,400 acres of Snow Canyon State Park are part of the larger Red Cliffs Desert Reserve, which was created to protect the habitat of the desert tortoise. The main activity to do for visitors of the park is hiking on 38 miles of trails. There is also a paved three-mile trail that allows bikes and 15 miles of equestrian trails.

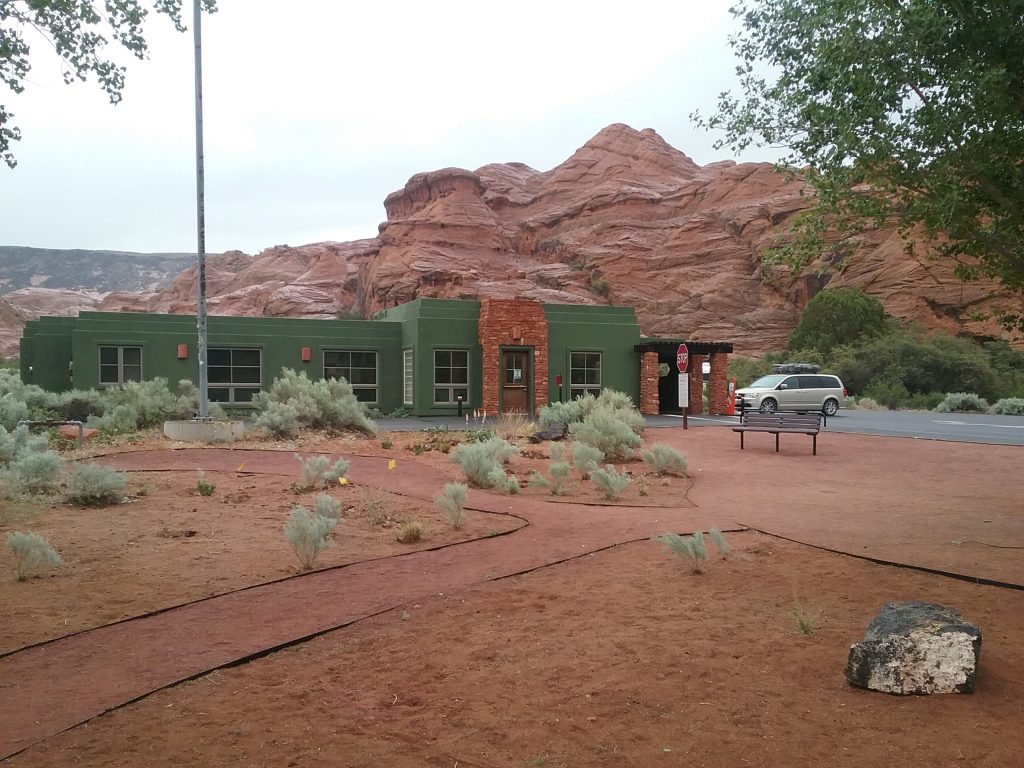

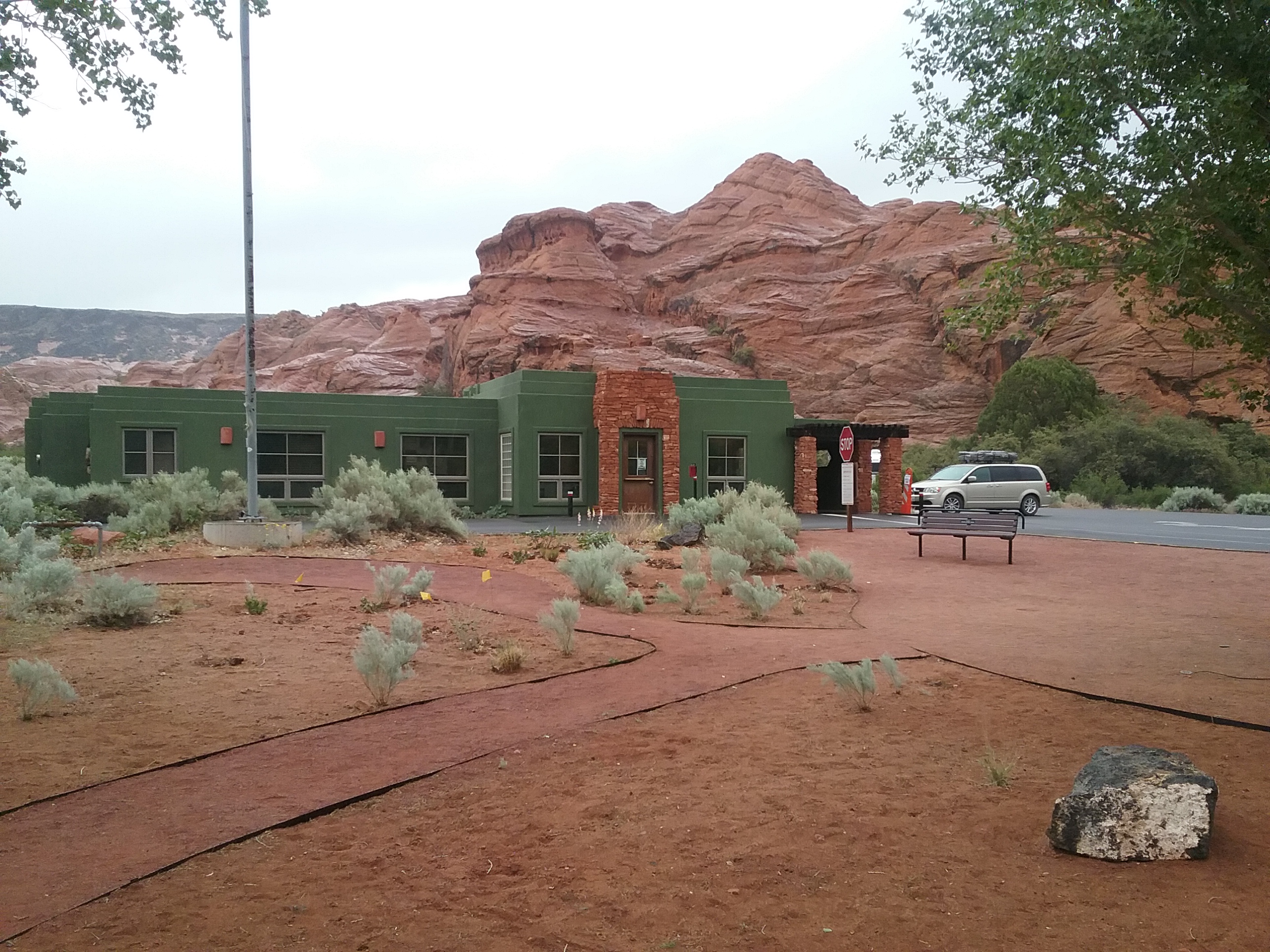

The park also includes several picnic areas, restrooms and a 33-unit campground next to the park headquarters.

Fall, winter and spring are the best times to visit, as summer temperatures are sometimes scorching.

For more information on Snow Canyon, visit the official park website.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Snow Canyon State Park Visitor Center shows a lone horse rider ascending Snow Canyon's dunes, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This photo of a historic photo on display at the Snow Canyon State Park Visitor Center shows horse rider gazing at the park's beauty, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Johnson Arch, the payoff at the end of the Johnson Arch Trail, which was apparently a popular picnicking spot for pioneers, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Stands of Navajo sandstone on the Johnson Arch Trail, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The contrast of fall colors and Navajo sandstone along the Johnson Arch Trail, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Carved textures on Navajo Sandsone in Jenny's Canyon, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, March 18, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The entrance of Jenny's Canyon, a short slot canyon at the south end of Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, March 18, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A perspective from the middle of Jenny's Canyon, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, March 18, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A set of sand dunes at the southern end of Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, May 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Looking south along Snow Canyon's main road after a rain storm, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, May 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Pioneer names, which date from 1881, written on sandstone in wagon axle grease, at the end of the Pioneer Names Trail, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, March 18, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The view south from next to the pioneer names at the end of the Pioneer Names Trail, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, March 18, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Lower Galoot Picnic area and its surroundings, as seen atop a Navajo sandstone outcropping nearby, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Oct. 19, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A showcase of the varied sandstone colors and volcanic ridges, as seen from the Upper Galoot Picnic Area, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Oct. 19, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Navajo sandstone contrasting with basalt ridges, Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Hikers scurry up ridges cut in the Navajo sandstone of Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The varied weathering patterns on the Navajo sandstone in Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Nov. 27, 2009 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A basalt rock sits atop a flow of Navajo sandstone in Snow Canyon State Park, Utah, Oct. 19, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News