FEATURE — On a winter day, Lee’s Ferry in Arizona is a serene place – a showcase of a wide, slowly flowing river contrasted by surrounding towering red rock cliffs. Only a few visitors walk along the trail near the riverbank taking in its majestic scenery.

This peaceful setting belies the bustling activity at this picturesque former river crossing during warmer months as well as the important role it played in history – the linchpin of the Mormon pioneer migration into the Arizona colonies.

The main reason for its significance over the course of its history is because it is the only place along the river for 700 miles with direct, easy access to the riverbank by land.

Lee’s Ferry, also identified as Lees Ferry, is also a geologic division point, basically where Glen Canyon ends and the Grand Canyon begins. It serves as an important point for the United States Geological Survey and Bureau of Reclamation to gauge streamflow between the upper and lower basins of the Colorado River in order to determine water allotments for members of the Colorado River Compact.

Today, it is best known for being ground zero for anyone taking a Grand Canyon river trip.

Earliest history

The first human inhabitants in the Lee’s Ferry vicinity were the Ancestral Puebloans, whose ruins in the area date back to approximately 1125 A.D. Later, Paiutes roamed the area and interacted with Franciscan friars Silvestre Velez de Escalante and Francisco Dominguez, who were the first Europeans to view the future Lee’s Ferry in October 1776.

Jacob Hamblin, Mormon trailblazer and missionary to the Indians, was the next white man to see the area, crossing the river near the future ferry for the first time in 1858. Hamblin participated in the first successful crossing of the river by ferry while on a mission to warn Navajos to stop raiding Utah settlers at what was then known as Pahreah Crossing in March 1864, building a raft sturdy enough to carry 15 men, their supplies and horses.

Hamblin realized that the future ferry site could be the doorway to Mormon expansion into eastern Arizona and encouraged Mormon church president Brigham Young to establish a permanent crossing to aid those potential pioneers. Young chose John D. Lee for the job and Lee gladly accepted, thinking it would be a great place to evade authorities seeking his capture for his role in the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Lee, along with his wives Emma Batchelor and Rachel Woolsey, moved to the ferry and started to eke out a living on what became known as the Lonely Dell Ranch, named for Emma’s first reaction at seeing the place.

Lee launched the first ferryboat, appropriately named the “Colorado,” in January 1873 and the period of 1873-1875 proved a busy one for the migration into Mormon Arizona colonies along the Little Colorado and Salt rivers. Another busy period came just after construction of the St. George Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was finished in 1877, prompting many couples from the southern colonies to make the trek north to solemnize their marriages in the temple on what became known as the “Honeymoon Trail.”

The church built what became known as Lee’s Fort in 1874, and it still stands today. The building served as a home, trading post and school for ferry operators’ families.

After being on the run from authorities for 17 years, Lee was captured in 1874 and eventually executed in 1877 for helping perpetrate the blackest chapter of Mormon history.

The trying life of ferryman Warren Johnson

Howard Spencer, the bishop of Long Valley — where Glendale, Orderville and Mt. Carmel lie — was tasked with choosing Lee’s successor as ferryman, finding prospects among those who were opposed to the United Order, a Mormon concept of community living, and found his man in Warren Johnson of Glendale. Johnson, however, was an unqualified volunteer, having no experience previously in the duties he would be assigned as ferryman. One thing he had going for him was he and his family hit it off well with Emma Lee, which helped him and his two wives, Permelia and Samantha, be successful and smoothed the transition.

In taking a page out of Hamblin’s book, Johnson became adept at getting along with the Navajos that would frequent the ferry, learning that laughing and joking with them while trading would get the job done, earning him the nickname Ba Hazhoona, or “Happy Man,” P.T. Reilly reported in his book, “Lee’s Ferry: From Mormon Crossing to National Park.”

Johnson learned the river’s nuances in a hurry and became the go-to expert on river crossings.

When the river’s water was high and powerful, Johnson only dared to take a more manageable skiff across the river, which necessitated taking wagons apart to fit on the smaller boat, leading to grumbling among many passing travelers.

On one occasion, May 24, 1876, a party led by Daniel H. Wells, counselor to Brigham Young in the First Presidency of the LDS church, wanted to cross the river as soon as possible to return to Salt Lake City after visiting the Arizona settlements, but Johnson warned against such a crossing on the regular ferryboat in such turbulent water and recommended taking the safer but much more time-consuming method of dismantling the wagons and putting them into the skiff. Impatient, Wells demanded that they cross in short order and they succeeded without incident in their first two crossings, but the third crossing proved disastrous when the party lost control of the boat in the river’s wrath, losing a few wagons and provisions and, more importantly, the life of Bishop Lorenzo Roundy.

Due to the dangers of venturing into the river in torrent stage on long, ungainly ferryboats with higher capacities, Johnson continually tried to convince the First Presidency to allow him to build an easier-to-manage, one-wagon capacity ferry, but to no avail. One time, they spurned his advice and “awarded” him with a 47-foot long boat.

“Johnson knew, when he saw the plan, that God had not inspired the brethren who designed it, but he said nothing and resolved to do his best,” Reilly wrote of this instance.

No one exactly knows if Johnson got approval from higher authorities or took it upon himself, but in the winter of 1886-87 he built his own one-wagon ferryboat.

At times, Johnson was doing the work of three men, having to tend the ferry and make a subsistence living from the farm. Some travelers ended up paying their ferriage through work, which was welcome to Johnson. In fact, he built small shacks with the express purpose of serving as accommodations for those laying over at the ferry. He convinced his brother-in-law, David Brinkerhoff, to be his partner at the ferry for approximately five years. During that period, Brinkerhoff was in charge of the farm so Johnson could devote most of his time to his ferry duties.

For a time, the ferry had two sets of ferry rates — the missionary rate, for Mormon immigrants, and the rate for “other travel.” For instance, in 1879, the missionary rate for a wagon and single team was $2 while for other travelers it was $3. A little later, however, all travelers were given the same rate.

One aspect of paying ferriage continued to haunt Johnson during his stay as ferryman. Some travelers paid their ferriage in perishable goods, which had to be consumed immediately by the ferryman’s family, leading to a debt to the church for the amount the perishables were worth. Johnson feared the brethren would eventually require him to pay this debt and wrote letters to Salt Lake seeking his status on the matter, letters whose replies did not address the issue or misunderstood it. Eventually, these debts were forgiven at the close of his service as ferryman.

The incident that shook Johnson and his family’s faith the most during their time at the ferry was the deaths of four of the Johnson children to diphtheria contracted from passing travelers in the spring of 1891.

“What have we done that the Lord has left us and what can we do to regain his favor again?” Johnson wrote in a heartfelt letter to then church President Wilford Woodruff on July 19, 1891.

Woodruff and his two counselors replied that Johnson had done no wrong, that the Lord loved him, and they likened his troubles to the trials of Job, Reilly reported in his book.

Another trial, indirectly started by Woodruff and church leadership, would eventually help lead Johnson away from the ferry. The manifesto ending the church’s practice of polygamy in 1890 caused great reflection in Johnson. Before the manifesto, federal authorities spared him from being prosecuted for practicing polygamy, but knowing now that it was church doctrine, he could not give up one of his two wives and their families. He left the ferry in 1896. His first thought was to flee all the way to Canada, but he eventually settled in Wyoming where he lived the final years of his life paralyzed after he broke his spine in a wagon accident. He died March 10, 1902.

Gold mining in red rock?

Just as silver was discovered in sandstone at Silver Reef in the 1860s, flecks of gold were discovered in the sands and gravel bars near the river banks in the vicinity of the ferry in the late 1800s. During the 1880s and 1890s, quite a bit of prospecting took place in the area.

“Some gold was found, but few, if any, struck it rich,” authors W.L. Rusho and C. Gregory Crampton noted in their book “Lee’s Ferry: Desert River Crossing.”

“Most prospectors soon discovered that expenses almost always exceeded income,” they wrote.

Two overly optimistic prospectors who had visions of striking it rich were Robert B. Stanton and Charles H. Spencer.

In 1899, Stanton built a mile-and-a-half road along the south river bank above the ferry and in 1900 installed a dredge to extract gold farther up the river near where Bullfrog Marina is now. By 1901, Stanton abandoned his operation.

Spencer came with his American Placer Corporation in 1910 and set up operations at Lee’s Ferry. He hoped to use high pressure hoses utilizing water pumped from the river to sluice the gold from the Chinle shale, sending that sluiced material by flume to an amalgamator set up to attempt to remove the gold. He even built a steamboat, dubbed the “Charles H. Spencer,” to transport coal along the river as fuel for his equipment.

Spencer’s steamboat became a microcosm illustrating his false optimism and failure. The craft, designed for much tamer rivers like the Sacramento, was not very successful in navigating the more powerful Colorado and was eventually beached and never operated again, succumbing to the unforgiving river over the years. So too, Spencer’s operation terminated by 1913.

The ferry in the 20th century

By the early 1900s, traffic at Lee’s Ferry had become practically a trickle, mostly locals. With the emergence of train travel, even though trips covered more miles, they took less time, which was preferable.

The LDS church sold its interest in the ferry to the Grand Canyon Cattle Company in 1909 and Coconino County, Arizona, took it over in 1910 (its first ferrymen under county ownership were Warren Johnson’s sons) operating it until June 7, 1928. At that time, its worst-ever accident killed three men, including Warren Johnson’s grandson Adolph, closing it for good. Even before the accident, similar past incidents had already become the impetus to start construction on a bridge in 1927.

From June 1928 to January 1929, when the bridge opened, highway travelers could not cross the river at any point between Moab and below the Grand Canyon. This, however, caused headaches for the bridge contractors as they had to send trucks on an 800-mile trip to cross the river at Needles, California, to arrive at a destination only 800 feet from the starting point, authors Rusho and Crampton noted in their book.

Starting in the 1930s and 1940s, the main purpose of Lee’s Ferry shifted to recreation, with river rafters and sport fishermen becoming its main clientele. Its place as a water recreation mecca was cemented in 1972 when it became part of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

Today, a typical morning at Lee’s Ferry between April and October features a crowded boat ramp with boaters and rafters and their guides readying themselves for an adventure on the river.

Visiting Lee’s Ferry

Lee’s Ferry is approximately 150 miles southeast of St. George. It is 46.8 miles east of Jacob Lake in northern Arizona on U.S. Highway 89A. Along the route, drivers pass through dramatic changes in scenery, from the forested Kaibab Plateau to the somewhat barren but picturesque House Rock Valley.

Before reaching Lee’s Ferry, visitors should stop at the Navajo Bridge Interpretive Center, open seasonally between March and October. The displays, markers and interpretive signs at the center will whet the visitor’s appetite for the history and scenery to come with visits to Lonely Dell Ranch and the ferry itself. Visitors should be sure to venture onto the historic Navajo Bridge for sweeping views of the river below and the towering Vermilion Cliffs surrounding the spot.

Before reaching Lee’s Ferry, a stroll to Lonely Dell Ranch will give visitors a sense as to what life was like for the families of ferrymen with its cabins and outbuildings, orchard and cemetery. At Lee’s Ferry itself, visitors can walk along the Lee’s Ferry Trail to view the area’s intact buildings from different eras, including Lee’s Fort, Spencer’s American Placer Corporation offices and buildings used by the U.S. Geological Survey. Along the trail, hikers can also see a boiler used by Spencer’s operation, the top of his steamboat peeking out of the water near the riverbank as well as an old cable used in later ferry operations.

Visitors hoping to enjoy a Grand Canyon rafting trip or guided fishing excursion should make reservations well in advance before they plan to come.

For more information on Lee’s Ferry, visit the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area website.

See more photos in the gallery below.

Click on a photo then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

Composite image of Lee's Ferry looking east towards the former upper crossing along the Lee's Ferry Trail today with inset of a historic photo of a Lee's Ferry river crossing in 1923. The modern photo is by Reuben Wadsworth and the historic photo is courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

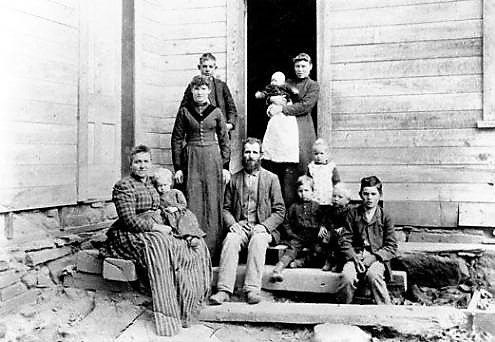

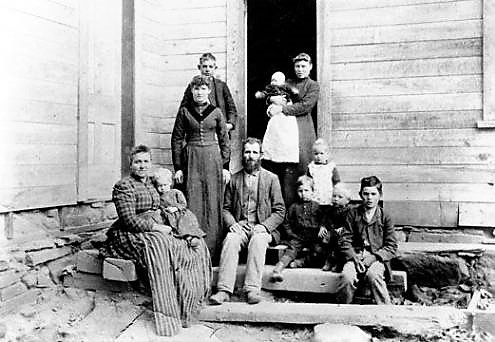

This historic photo shows Warren Johnson (center with beard) posing with his family at Lonely Dell Ranch near Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1890 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows the two-story Johnson family home at Lonely Dell Ranch. The home burned down in the 1920s, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1892 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows the Johnson children's graves at the Lonely Dell Cemetery, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, circa 1943-1970 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

Plaque dedicated to the memory and service of Warren Johnson, the dedicated ferryman at Lee's Ferry for over 20 years in the late 19th century, Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This historic photo on an interpretive sign shows a typical river crossing via ferryboat at Lee's Ferry, Arizona, circa 1890s, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

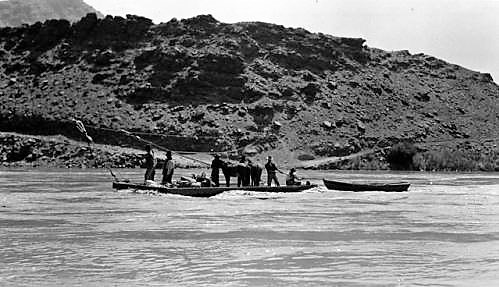

This historic photo shows a river crossing at Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

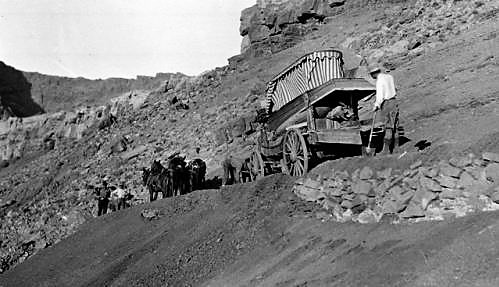

This historic photo shows a wagon negotiating Lee's backbone, a steep incline just before reaching the ferry about which many ferry goers grumbled, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows mining equipment used by workers for Charles H. Spencer's American Placer Corporation, a failed try at gold mining from 1910-1912, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows mining equipment used by workers for Charles H. Spencer's American Placer Corporation, a failed try at gold mining from 1910-1912, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows a boiler used by Charles H. Spencer's American Placer Corporation, a failed try at gold mining from 1910-1912, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows the ferryboat "Charles H. Spencer," used to transport coal to fuel the mining equipment of Spencer's failed gold mining operation, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910-1912 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows a ferryboat crossing with a car, Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1910-1924 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

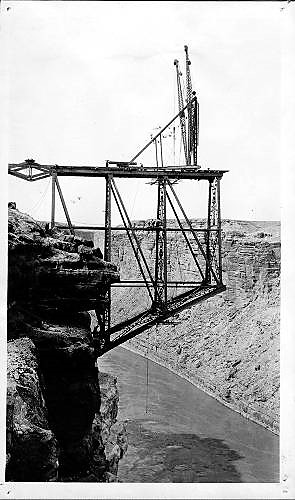

This historic photo shows Navajo Bridge under construction, Marble Canyon, Arizona, 1927 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows the Navajo Bridge soon after construction from river level, Marble Canyon, Arizona, 1929 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

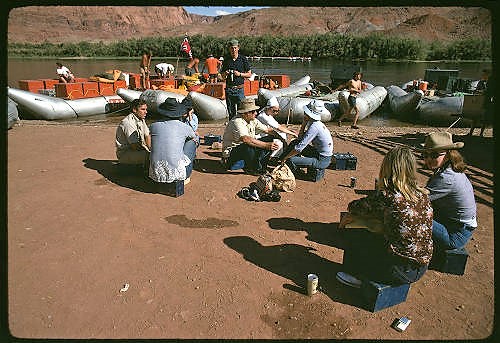

This historic photo shows Grand Canyon river rafters rigging their crafts, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, 1975 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

This historic photo shows river rafters after having pushed off from Lee's Ferry, Arizona, 1950-1970 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library P.T. Reilly Collection, St. George News

Navajo artisans try to sell their wares on the east side of Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Visitors view Marble Canyon from the 1929 Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Both Navajo Bridges, seen side by side near the Navajo Bridge Interpretive Center. The one on the left, finished in 1929, now serves as a footbridge for visitors to traverse and view the canyon. The one on the right, finished in 1995, is wider and built to carry the heavy loads of today's traffic along U.S. 89-A, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The new Navajo Bridge, finished in 1995, stretches across Marble Canyon, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Navajo Bridge Interpretive Center with the Vermilion Cliffs behind it, Marble Canyon, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Colorado River as it flows through Marble Canyon looking east from the Navajo Bridge, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Entryway to Lonely Dell Ranch, where the ferrymen's families lived and farmed during the ferry's heyday, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Wagon and Samantha Johnson cabin at the Lonely Dell Ranch, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Wagon and Samantha Johnson cabin at the Lonely Dell Ranch, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lonely Dell Ranch Orchard looking east towards rising vermilion cliffs, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lee's Ferry as seen from the beginning of the Lee Trail, which follows the bank of the river to what was once the upper ferry site, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lee's Ferry looking west at dusk, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lee's Ferry Fort, built in 1874, is one of the oldest surviving relics from the ferry's heyday in the late 19th century, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Former offices of the American Placer Corporation, Charles H. Spencer's name for his failed gold mining operation at Lee's Ferry, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The remains of the boiler used in Charles H. Spencer's failed gold mining operation, between 1910-1912, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Lee's Ferry looking east towards the former upper crossing, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona, Jan. 1, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2019, all rights reserved.

Great article, excellent photos. Thank you.

(As fyi, the author may need to correct the second “800 mile” reference in the paragraph about the bridge construction.)

Terrific piece Mr. Wadsworth. Thanks again.

Outstanding article and made vivid and alive with the photography. This spring I will journey, once again, to the Vermilion Cliffs, and Lee’s Ferry. With much gratitude, thank you.

Thank you Mr. Wadsworth for a very interesting article. I’m a great grandson to Warren Johnson and my mother was born in Lee’s Ferry. I’ve heard a lot of stories about the place and what it was like living there but still learned a few things and saw some pictures I’ve not seen before in your article. Well done and thank you.

Thank you all for your kind words about this story. It was truly a fun and interesting one to write. And “holger,” I have corrected the second 800-mile reference. Thanks for pointing it out.

Love Mormon pioneer history, thank you for the wonderful article, it was very nicely done

Great article, Reuben! Thank you for your in-depth and interesting articles.

Masterful reporting, as usual. This is the work of a true historian, more than the prose of an article one is able to sense the feelings, and emotions, that Mr Wadsworth is able to infuse into his reporting.