ST. GEORGE — The growing recognition that physical, mental and social challenges are interrelated has finally led to the integration of behavioral health and physical health care in Utah, offering new hope for many where there once seemed there was none. Additionally, a new law takes effect Thursday, emphasizing treatment programs instead of punishment for criminal offenders.

Behavioral health conditions are extremely common, affecting nearly 1 in 5 Americans, but often, health care providers lack the time, training and staff resources to recognize and treat behavioral health conditions.

Unfortunately, physical and behavioral health care systems tend to operate independently without coordination between them, leading to gaps in care or inappropriate care.

The good news: Change is happening in Utah in a variety of innovative and creative ways.

The idea that medical professionals of all specialties should work together to treat the range of ailments a patient might be experiencing at one time is expected to result in a more comprehensive way to treat the patient as “a whole person” and provide better care for individuals and families.

In order to further discuss and implement cutting-edge solutions to behavioral health services, the Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health and the City of St. George were hosts to more than 900 professionals from 18 states during the Utah Fall Substance Abuse Conference, a three-day educational event held last week at the Dixie Center St. George.

“There’s a lot of new excitement over our state’s transition with health care expansion where people are going to have health insurance — hundreds of thousands of people — for the first time,” said Jeff Marrott, public information officer for Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health. “And, judicial reform, our state is really taking the lead in the nation in transforming the way we do business. Instead of punishment now, we’re all about treatment and rehabilitation.”

Key discussion items at the conference included plans for the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, changing criminal offender behaviors as well as prevention and recovery supports for substance-use disorders and related conditions.

Health care model

“The prevailing tendency in today’s health care system is to treat medical and behavioral health conditions, including mental health and substance use disorders, as if they occur in different domains rather than within the same person,” according to a report commissioned by the American Psychiatric Association.

Because of fragmented care, general medical costs for treating people with behavioral comorbidities are two to three times higher — an estimated $283 billion in 2012 — than treating physical health conditions only.

The use of an integrated public health care model could save $26-$48 billion annually in general health care costs and is a smart strategy to enhance public safety, Department of Vermont Health Access Chief Medical Officer Tom Simpatico said.

In the integrated model, psychiatric physicians, primary care physicians and other behavioral health providers work together with patients and families to provide quality care, Simpatico said, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to coordinate care.

The public health model applications are also being used in a rapidly growing array of complex systems applications including veterans’ services, as well as helping Utah reform its criminal justice system, Simpatico said.

“States are eager to combat the rising prison health costs driven by an aging population, high incidents of crimes and disease,” he said, “and they’re also eager to move people out into the community to an expanding array of social services and health care services that would cut down on recidivism and use federal dollars to subsidize state dollars.”

In particular, Simpatico said, for ex-inmates with severe mental health and substance abuse issues, immediate access to health care services upon or, ideally, prior to release, helps to substantially reduce recidivism.

Justice Reinvestment Initiative

In response to Gov. Gary Herbert’s challenge to reduce recidivism along with the introduction of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, Utah’s behavioral health efforts are now using evidence-based findings and new information to begin to focus on both criminogenic and behavioral health screens.

In April, Herbert signed House Bill 348 into law — a law aiming at reforming Utah’s criminal justice system, emphasizing treatment programs instead of punishment for criminal offenders. The new law takes effect Oct. 1.

“For a long time, we just thought people who commit crimes are bad — lock ‘em up,” Ron Gordon, executive director of Utah’s Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice, said. “And then, recently, we started realizing that there are other things that can contribute sometimes to criminal behavior — they don’t excuse it, but they can contribute to it — so we realized, one of those things is substance-use disorders. Another is mental health disorders.”

According to an extensive Utah-specific data analysis, about one-third of the prison population is from new court commitments; two-thirds of them are there because they broke a condition of their probation or parole.

“Those who are returning to prison after being paroled — so they go to prison, they get out on parole — half of them go back and half of those are for a technical violation rather than for a new crime,” Gordon said, adding:

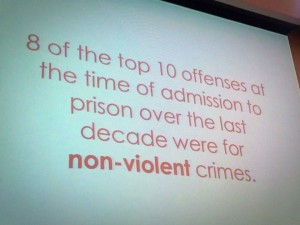

Sixty-three percent of the new court commitments admitted were for nonviolent crimes. Eight of the top 10 offenses at the time of admission were for nonviolent crimes. Nonviolent offenders make up 41 percent of the prison population.

The reforms are expected to eliminate almost all projected prison growth over the next 20 years and save about $540 million.

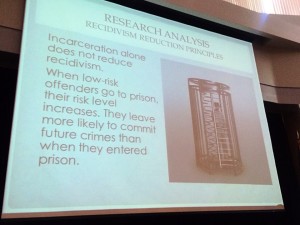

“Incarceration by itself does nothing to reduce recidivism,” Gordon said. “When low-risk offenders go to prison, they come out higher-risk. We wish it went the other way. It doesn’t.”

Supervision should be focused on the risk level of the individual offender, Gordon said, and treatment needs to be based on individual needs of the specific person.

“So we don’t have these one-size-fits-all approach that are very convenient,” he said, “just not terribly productive.”

Other foundational principles for new sentencing guidelines include using both sanctions and rewards, frontloading the resources, balancing supervision and treatment and using swift certain and proportionate sanctions.

The study also concluded that longer lengths of stay in prison do not correlate with reduction in recidivism.

“So here’s kind of a summary that we got to,” Gordon said:

It’s not only OK to take care of people, but it’s actually one of the most effective ways to reduce recidivism. Every person is unique with their own needs and risks. We get better results when we treat people rather than offenses. People respond better when we address their unique needs in the community than when we put them in prison.

“Some of these things seem like things maybe you learned in elementary school,” Gordon added. “Sometimes it takes the criminal justice system a little bit of time to catch up.”

The commission then came up with policy recommendations that include focusing prison beds on violent offenders, strengthening probation and parole supervision, improving and expanding re-entry and treatment services, supporting local corrections systems and ensuring oversight and accountability.

All offenders booked into jail will receive an initial screening that addresses their criminogenic risks, their substance-use needs and their mental health needs. In addition, possession of a controlled substance will be a class A misdemeanor rather than a felony on the first and second convictions.

Drug-free zones will also be restructured, Gordon said.

“I’m going to use this one as an example of how policy can kind of run amok sometimes when we don’t check ourselves,” Gordon said. “Drug-free zones were intended to enhance penalties for drug crimes that took place in areas where children would likely be present because we were afraid that dealers were dealing to children. And so we said ‘OK … if you deal drugs on elementary school grounds that’s a drug-free zone. And near a daycare, drug-free zone. And by a church, that’s a drug-free zone. And let’s throw in malls because those are dangerous and parks,’ and we just thought ‘this is great … drug-free zones are wonderful.’”

Gordon then showed a map of what the state looks like with all of its drug-free zones, showing how there was no meaningful distinction between crimes committed in drug-free zones and crimes committed anywhere else.

“So there was a little area in Sanpete County that was not a drug-free zone,” Gordon said. “You can’t get there on foot, but there’s a little tiny area, and it just got out of hand.”

Drug-free zones will be narrowed with a focus on what they were originally designed for, and drug possession is no longer subject to these drug-free zone enhancements.

The initiative will also establish a system that allows offenders to earn their way off probation by complying with the terms of probation and will allow inmates to earn an earlier release by completing programs that reduce their risk level. Gordon said:

We’re not just treating the crime and we’re not just treating the substance-use disorder — we’re treating all of those root causes of the choices that people are making, and that’s really fundamental stuff, and it’s really hard stuff. It’s much harder than just putting somebody in prison, but the research is absolutely clear that if we want to reduce recidivism, that’s where we focus — we focus on the person as a whole.

“We’re not suggesting that we simply turn our backs on crime, that we turn a blind eye to everything that’s going on in the criminal justice system,” Gordon said. “We are suggesting that we can’t turn our backs on people.”

Judge Kathleen M. Nelson Justice Award

Ron Gordon was honored at the conference and presented with the Judge Kathleen M. Nelson Justice Award. The award recognizes individuals who, through their work or involvement with the legal system, have made a significant contribution to improve the quality of life of those struggling with substance-use disorders and have enhanced the health of the community.

Gordon told a story about a man he had recently met while taking a tour of a therapeutic community in Salt Lake City.

“At the start of the tour, a man named Paul met me at the door,” Gordon said. “I was dressed in casual Friday clothes. He had on a dress shirt and tie. I assumed he was the director or manager of the program there.”

After talking for quite some time, it wasn’t until the end that Gordon said he realized Paul was a resident at this therapeutic community. Paul told him his life story, Gordon said.

“He told me about how he had been arrested on a number of violent crimes that were fueled by drug addiction that had a number of contributing factors,” Gordon said. “… Everything that could have gone wrong, seems to have gone wrong. He grew up in a tough area, in a tough neighborhood where it was expected that you were either going to act or be acted upon, and so he learned defense mechanisms that were not particularly healthy.”

Paul had a successful job and a family, Gordon said, but couldn’t get away from his substance-use disorder, which led him to commit multiple aggravated burglaries.

“He was facing five-to-life on a number of counts,” Gordon said, “and he stood before the sentencing judge in shackles — not just handcuffs because he’d been convicted of violent crimes, so he had ankle shackles on and he had wrist shackles on and they were shackled at the belly — and he looked at his mother. His mother was crying and he said: ‘I thought to myself, I have got to change, but I don’t know how to change. I guess I won’t change.’”

The judge fortunately saw some hope and took a chance, Gordon said, sentencing Paul to probation and the therapeutic community for nine or 10 months.

“This is the guy you’d have over for dinner to your home,” Gordon said. “He’s a great man. You want to be around him because he is uplifting and inspiring, and it was great to be there and remember that this is about way more than policies. And it’s about more than committees. It’s about human beings and it’s about changing lives — saving lives.”

Gordon accepted the award on behalf of his staff and his “new friend Paul at the therapeutic community.”

Related posts

- Utah considers major criminal justice reform, reduced drug offense charges

- Voices of Recovery: Young family finds hope amid drug addiction

- Voices of Recovery: Prevention works, treatment is effective, recovery is possible

- Drug-free zones: What, where are they? What is their purpose? STGnews VideocastCommunity campaigns support addiction recovery; schedule of events

- Council recognizes Recovery Awareness Month, approves Windmill Plaza

- Get your red boots on: George, Streetfest is going country, celebrates recovery

- Fighting addiction, promoting recovery in Southern Utah; community events and resources

- Relationship Connection: Opening up about an addiction

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2015, all rights reserved.

I have really mixed emotions on this one. If people have a drug problem I think we should help them, not jail them. However, if they have a drug problem that causes them to resort to burglary, theft, and other crime, they should go to jail or prison just like anyone else. The punishment should fit the crime, not the reason for the crime (justice is supposed to be blind, after all). I also think our prisons need to be revamped to suck a lot more in terms of what they offer (ie. be less comfortable and involve a lot more hard work and benefiting of society), but they should also protect the inmates from each other a lot more. I’d rather be executed than go to prison if I couldn’t be put in solitary some where. Being sold for a pack of cigarettes shouldn’t be part of the sentence.

Treatment instead of punishment is the right thing to do however if they are also violent then punish first treat later.

prison industrial complex wants inmates. its all about $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$